Lady Margaret Beaufort Fellows are elected by Governing Body in recognition of their commitment to the College. This list of the Lady Margaret Beaufort Fellows of Christ's College is ordered by date of election.

by Stephen Harrison, m.2006)

Gilbert Laird Jessop (19th May 1874 – 11th May 1955) is perhaps the greatest cricketer you’ve never heard of. Between 1894 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he played 493 First Class matches and represented England in 18 Tests, scoring over 26,000 runs with 569 of them coming in international matches. However, numbers alone - Jessop averaged an altogether unexciting 21.88 for England - don’t tell the full story. Jessop was an entertainer, a man whose ferocious hitting abilities delighted crowds and dismayed bowlers, a man whose scoring rate dwarfs household names like Hobbs and Bradman.

Gilbert Laird Jessop (19th May 1874 – 11th May 1955) is perhaps the greatest cricketer you’ve never heard of. Between 1894 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he played 493 First Class matches and represented England in 18 Tests, scoring over 26,000 runs with 569 of them coming in international matches. However, numbers alone - Jessop averaged an altogether unexciting 21.88 for England - don’t tell the full story. Jessop was an entertainer, a man whose ferocious hitting abilities delighted crowds and dismayed bowlers, a man whose scoring rate dwarfs household names like Hobbs and Bradman.

His most famous innings came during the 5th Test against Australia at the Oval in August 1902. England were chasing 263 to win in the final innings but had been reduced to 48 for 5 when Jessop came to the wicket. In his characteristically swashbuckling style, Jessop immediately set about the Australian attack. A little over an hour later he was dismissed for 104. His 76-ball, 77-minute century is one of the fastest ever – had the rules of cricket awarded a 6 rather than a 4 when a ball cleared the boundary in 1902 as they do now, the statistics would be even more staggering. A bowler as well as a batsman, Jessop took over 800 First Class wickets before developing a serious heart problem whilst serving in World War I, which prevented the resumption of his career in 1919.

Jessop’s cricketing career either side of his time at Christ’s is fairly well chronicled by the links below, but the survival of end of term reports in the College Magazines of the period enable us to make some observations about his time at Christ’s. He matriculated in 1896 just in time to join the cricket team for the season and made an immediate impression, scoring 433 runs from 8 innings and taking 29 wickets for 263 runs. Most impressive was his staggering 212 not out, out of a team score of 281-7, against Clare. He followed this with 50 against St John’s and 109 against Corpus. The writers of the end of season report, published in the Michaelmas edition of the magazine, were effusive in their praise, describing him as a ‘most brilliant batsman of the hitting order. Excellent fast bowler with wonderful knack of bumping. Fine field anywhere.’

Given that he had played First Class cricket before coming up to Cambridge, he inevitably represented the University from the very start; this limited him to 3 appearances for Christ’s in each of the next two seasons. He managed 149 runs in 1897, including a century in a comfortable victory over Magdalene, but struggled with the bat in 1898, scoring just 38 runs with a top score of 29. However, he more than compensated with the ball, taking 19 wickets at a cost of just 42 total runs in 1898. The statistics speak for themselves to the extent that the writer of the end of season player reports simply wrote, ‘nothing can be added to his previous characters.’

In the winters, Jessop represented the college at association football, initially as a goalkeeper and later as a defender. A report of 1899 describes him as ‘invaluable’ and bemoans his absence (for unspecified reasons) from the side during the first half of the season.

By the time he left Cambridge in 1899, without taking a degree, Jessop had already been named one of Wisden’s ‘Cricketers of the Year’ for 1898, and would shortly make his England debut.

Further Information (all links are to external websites)

More information about sport in Christ’s during Jessop’s time at the college can be found here.

Wisden’s obituary of Jessop after his death in 1955 can be found here, whilst an excellent article on his career can be found here. His first class statistics are recorded here.

Complete College Statistics

Batting

|

Year |

Innings |

Not Out |

Runs |

Average |

|

1896 |

8 |

1 |

433 |

61.9 |

|

1897 |

3 |

0 |

149 |

49.67 |

|

1898 |

3 |

0 |

38 |

12.67 |

|

Total |

14 |

1 |

620 |

47.69 |

Bowling

|

Year |

Runs Conceded |

Wickets |

Average |

|

1896 |

263 |

29 |

9.1 |

|

1897 |

46 |

8 |

5.8 |

|

1898 |

42 |

19 |

2.2 |

|

Total |

351 |

56 |

6.27 |

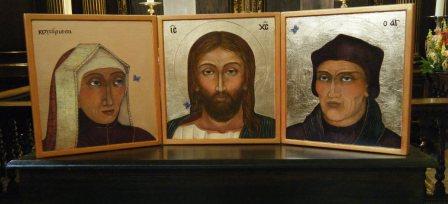

The Icon of Our Lord, St John Fisher and The Lady Margaret

On Sunday 5 June, the Sunday nearest to the anniversary of the Consecration of the College Chapel, the Bishop of Ely, the Rt Revd Stephen Conway, blessed and dedicated a newly written 'triptych' icon for the College Chapel. The icon was crafted by Roy and Jenny Summerfield of Lincoln.

Interpreting the Icon

The icon is a triptych, which means that it is made up of three panels. It is written in the Eastern Orthodox style. It is painted with a gold-leaf background with warm and mellow colours for the figures. The common denominator of the face has been chosen.

The central panel represents Christ, who gazes forward to make direct eye contact with us.

The left hand panel shows Lady Margaret Beaufort, the Foundress of the College, who gazes directly towards Christ as Saviour.

The right hand panel shows John Fisher, who was Lady Margaret’s Confessor and the first Visitor of the College. John Fisher gazes outwards, but not directly at us. This outward gaze provides engagement and immediacy. Both the eye-levels of Lady Margaret and John Fisher are slightly lower than that of Christ, signifying Christ’s Lordship and divinity.

Another interesting feature of the icon is that a Common Blue butterfly appears on all three panels. This is a small but vivid creature found in the

The overall effect is that through our Saviour Jesus Christ, his followers (Lady Margaret, John Fisher and every one of us) become catalysts for new life and fresh hope, despite the trials and difficulties that we all face.

John Philipps Kenyon

1927-1996

John Kenyon was Lecturer in History at Cambridge (1956-62), and Professor of Modern History at the Universities of Hull (1962-1981), St Andrews (1981-7) and Kansas (1987-94). He authored nine books, a number of essays and twice edited titles, his work focussing on the early and late seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century. An elegant and witty prose stylist he contributed essays and reviews to titles such as The Observer and The Spectator. At the early age of thirty-five he was granted the G.F. Grant Chair at Hull and a Fellowship of the British Academy in 1981.

John Kenyon was born in Sheffield on 18 June 1927 and maintained the manner of a blunt, sceptical Yorkshireman throughout his life, but he could also be a lively conversationalist and drinking companion. He attended King Edward VII Grammar School in Sheffield and progressed to Sheffield University receiving a First Class Degree in 1949. He habitually attended Anglican worship, often reading the lessons and was a member of the Prayer Book Society. He once successfully defended the 1701 Act of Settlement on the Radio 4 Programme You the Jury.

After graduating he began research on seventeenth-century history at Sheffield under Professor George Potter. His research focussed on the political career of the Second Earl of Sunderland. After interest from Dante Campailla and Professor Jack Plumb, Kenyon received the Lloyd studentship and took his place at Christ’s College in October 1950. Plumb quickly promoted him for a Research Fellowship at Christ’s and shortly he was granted a University Assistant Lectureship. He later became Director of Studies in History and in 1961-62 was Christ's nominee as Junior Proctor.

During his seven years in the Cambridge History Faculty Kenyon lectured mainly on 'English Constitutional History 1603-1760', material from which was disseminated to several generations of students in his volume 'The Stuart Constitution: Documents and Commentary' (1966). He also taught a final-year special subject on'James II and the Revolution of 1688-9'

According to John Morrill, Fellow of the British Academy, in his biography of John Philipps Kenyon in the Proceedings of the British Academy (1999):

‘John Kenyon had the best historical intelligence of his generation. He understood men and women in the past and he wrote about them with a rare precision, clarity and conviction. He was a productive scholar and all his works except one wore their learning with a deceptive lightness. He fitted into no school, reacted against fashion, came to look old-fashioned in his interests. He was a magnificent historian who could not quite build on the brilliance of his early promise, but who greatly underestimated the magnitude of his own achievement and the continuing appeal of his writing’ (p.460)

Kenyon was best known to the wider public through 'The Stuarts' (1958), in its day an influential general history, and 'The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance' (1983), whose vivid pen-pictures grew out of earlier writings for The Observer.

John Kenyon was Lecturer in History at Cambridge (1956-62), and Professor of Modern History at the Universities of Hull (1962-1981), St Andrews (1981-7) and Kansas (1987-94). He authored nine books, a number of essays and twice edited titles, his work focussing on the early and late seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century. An elegant and witty prose stylist he contributed essays and reviews to titles such as The Observer and The Spectator. At the early age of thirty-five he was granted the G.F. Grant Chair at Hull and a Fellowship of the British Academy in 1981.

John Kenyon was born in Sheffield on 18 June 1927 and maintained the manner of a blunt, sceptical Yorkshireman throughout his life, but he could also be a lively conversationalist and drinking companion. He attended King Edward VII Grammar School in Sheffield and progressed to Sheffield University receiving a First Class Degree in 1949. He habitually attended Anglican worship, often reading the lessons and was a member of the Prayer Book Society. He once successfully defended the 1701 Act of Settlement on the Radio 4 Programme You the Jury.

After graduating he began research on seventeenth-century history at Sheffield under Professor George Potter. His research focussed on the political career of the Second Earl of Sunderland. After interest from Dante Campailla and Professor Jack Plumb, Kenyon received the Lloyd studentship and took his place at Christ’s College in October 1950. Plumb quickly promoted him for a Research Fellowship at Christ’s and shortly he was granted a University Assistant Lectureship. He later became Director of Studies in History and in 1961-62 was Christ's nominee as Junior Proctor.

During his seven years in the Cambridge History Faculty Kenyon lectured mainly on 'English Constitutional History 1603-1760', material from which was disseminated to several generations of students in his volume 'The Stuart Constitution: Documents and Commentary' (1966). He also taught a final-year special subject on'James II and the Revolution of 1688-9'

According to John Morrill, Fellow of the British Academy, in his biography of John Philipps Kenyon in the Proceedings of the British Academy (1999):

‘John Kenyon had the best historical intelligence of his generation. He understood men and women in the past and he wrote about them with a rare precision, clarity and conviction. He was a productive scholar and all his works except one wore their learning with a deceptive lightness. He fitted into no school, reacted against fashion, came to look old-fashioned in his interests. He was a magnificent historian who could not quite build on the brilliance of his early promise, but who greatly underestimated the magnitude of his own achievement and the continuing appeal of his writing’ (p.460)

Kenyon was best known to the wider public through 'The Stuarts' (1958), in its day an influential general history, and 'The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance' (1983), whose vivid pen-pictures grew out of earlier writings for The Observer.

James Meade was one of the great economists of the 20th century. It was Keynes’s vision and genius which underlay the reconstruction of economics in the interwar period, and provided the basic analytical framework which economists have used since for understanding macroeconomic growth and fluctuations. But James Meade’s contribution was almost as important: he helped to make Keynes’s framework operational, by developing the first modern set of national accounts, and he extended it to incorporate the international trade and capital flows which characterise the late 20th century globalised economy. It was his work on the Theory of International Economic Policy, published in 1951-55 when he was teaching at LSE, which was cited when he was awarded a share of the 1977 Nobel Prize in Economics.

James began his academic career in traditional fashion, studying Classics at Oxford. Appalled by the intractable problem of high unemployment in interwar Britain, he switched to Economics (then a very new subject in Oxford), and graduated in 1930 with a First in PPE. He was elected immediately to a Fellowship at Hertford (his undergraduate College), and sent to Cambridge for a year ‘to learn my subject before I began to teach it’. While in Cambridge he became a member of the famous ‘Circus’ of young economists which was trying to think through and develop the ideas which Keynes had just published in the Treatise on Money. James made a fundamental contribution to this process, in the form of what was then known as ‘Mr Meade’s Relation’, which forms the basis (with due acknowledgement) of much of Richard Kahn’s original explanation of the Keynesian multiplier. With typical modesty James downplayed his ideas, described by Kahn in 1931 as ‘as yet unpublished’, and they only appeared in print in 1993.

James returned to Oxford in 1931, and spent the next six years teaching Economics, developing and publishing his ideas about what is now called macroeconomics, and writing an early and very sophisticated textbook on modern economics. He was also involved in formulating policy proposals for the Labour party (then a tiny minority in parliament) and in the League of Nations Union. It was through his work for the League of Nations that he met Margaret Wilson, and they married in 1933. In 1937 James took leave of absence from Oxford to work in Geneva writing the League’s annual World Economic Survey: this was an opportunity to use his theoretical ideas to evaluate the varied policy strategies which governments had adopted in the turmoil of the Great Depression.

James and his family returned to England with much drama in May 1940, just as the German army was conquering France, and he took up a job in what became the Economic Section of the War Cabinet. During the next six years, working closely with Keynes and others, he made three major practical contributions to the new economic thinking which would underly the post-war world. With Richard Stone he developed the first modern system of national accounts, the essential information needed for coherent economic policy-making. He played a vital role in the complicated process which led to the famous White Paper on Employment Policy: this established full employment as an objective of Government policy in the UK, a symbolic rejection of the ‘do-nothing’ approach to unemployment which had led James to become an economist fifteen years earlier. Finally, he took the leading role from the British side in the Anglo American discussions on post-war commercial policy, working for the establishment of an International Trade Organisation which would foster a return to multilateral trade in place of the damaging experiments with bilateralism and autarchy which had characterised the 1930’s. The ITO was intended to complement the two ‘Bretton Woods’ organisations (the IMF and World Bank), but political complications meant that the treaty establishing it was not ratified. However many of the key principles were incorporated in the GATT, and the original vision of an international organisation ultimately led to the establishment of the World Trade Organisation in 1995.

Although James continued as a government adviser in the immediate post-war period, he found it difficult to work with Ministers who were, for a variety of reasons, strongly attached to the continuation of wartime controls and rationing, and he resigned in 1947 to take up a Chair at the London School of Economics. The books which he published while at LSE, for which he was subsequently awarded the Nobel Prize, form the basis for much of what is now taught as International Economics: they cover the relationships between domestic and international balance in the economy, the rationale for preferential trade agreements such as those which led to the formation of the EU, and many other topics which are still relevant today.

In 1957 James moved to Cambridge to take up the Chair of Political Economy which had previously been held by Marshall, Pigou and Denis Robertson. At the same time he became a Professorial Fellow of Christ’s, and began his association of nearly 40 years with the College. The University Statutes of the time did not allow Professors to supervise undergraduates, so that for most Christ’s undergraduates he was inevitably a remote, though kindly and courteous, figure. James remained a Fellow of Christ’s until his retirement in 1974, and was then made an Honorary Fellow.

The move to Cambridge also brought James into the acrimonious politics of the Economics Faculty, a change which he did not enjoy. Looking back, it is clear that the debates reflected not only the combative personality of some of the key participants, but also deep intellectual differences about the ways in which Keynes’s original insights should be developed. For James, economics was about moderate and carefully designed reforms which would make a market economy fairer and more efficient, and which would allow growth with stable prices and full employment. But for others, who saw themselves as the guardians of the ‘Cambridge’ tradition, Keynes’s key contribution had been to show that, since financial markets could not allocate capital efficiently (either within a single country, or across international borders), most forms of investment should be the outcome of a government-led planning process.

Conflicts within the Economics Faculty, and the wish to focus on his research and writing, led James to resign his Chair in 1968, and to take up a Senior Research Fellowship at Christ’s. During his time in Cambridge he had started to write a comprehensive multi-volume Principles of Political Economy (perhaps the last book to use this traditional title), but the problems raised by the rapid expansion of the subject, together with a renewed interest in policy issues, meant that it was never completed. Instead James chaired a high-powered, but independent, committee on the reform of the UK tax system: many subsequent tax changes can be seen as (unacknowledged) moves towards implementing the reforms which the committee had suggested. And, in response to the mid-1970’s retreat from Keynesian demand management, at the age of 70 he gathered a group of young economists to work on new approaches to the formulation of macroeconomic policy, which would allow the control of inflation without generating unacceptable levels of unemployment or gross inequalities in income. The ideas which James and other members of this group developed have also had a major, though indirect, impact on the way in which policy makers in the UK operate.

Experimental studies of economists have, regrettably, suggested that they are disproportionately likely to follow the teachings of their subject and focus on individual rewards. James was always an outstanding counterexample to this tendency, seeing economics as a way of thinking about problems which should inform policy choices and foster the welfare of all. One of his last published works, Agathotopia, described his visit to ‘the island of Agathotopia . The inhabitants made no claim for perfection in their social arrangements, but they did claim the island to be a Good Place to live in. I studied their institutions closely, came to the conclusion that their social arrangements were indeed about as good as one could hope to achieve in this wicked world, and returned home to recommend Agathopian arrangements for my own country’. Sadly, it is hard to conduct this sort of social experiment in economics: so we will probably never know whether, in a wicked world where most of us lack James’s moral compass and integrity, Agathotopia is truly feasible.

History of Christ's College / Undergraduate Economics at Christ's

A brief History of the Visual Arts Centre at Christ’s College – by Alan Munro

In 1997, I was approached by the Director of Kettle’s Yard, Michael Harrison, enquiring if by any chance the College had space to house a Video artist called Marion Kalmus for a year. I had, for a long time, felt that the University and College provide outstanding opportunities for sport, music and drama, but very little for the visual arts. I had also identified the space on the first floor above the furniture shop on King Street as unsuitable for commercial letting. Kettle’s Yard were willing to pay a modest rent and our Maintenance Manager (then Tony Weaver) felt that it would be very easy to make part of the space suitable for Marion Kalmus’ work. In this way the Art Centre started.

Kettle’s Yard expressed an interest to rent space again for the next academic year, and the College Council agreed that the Maintenance Department could spend a modest sum working in the summer to convert the whole of the first floor into three large studios. Also at this time the College was extremely fortunate to receive a donation from Ruben Levy and Shelby White, which together with funds from Sir John Plumb, created the Levy Plumb fund, which agreed to fund a graduate studentship in the Visual Arts with the first appointment in the summer of 1998.

Somehow I felt that we should be able to use the third studio to make sure that Christ’s students would get the opportunity, and be encouraged, to try life drawing. Again, I was approached by Issam Kourbaj, a Cambridge artist who was looking for studio space to rent. Issam has had many years experience as a teacher to people at all levels of ability. The Council agreed that I could offer Issam one of the studios free of rent on condition that he provided life drawing classes for Christ's College students. Much has changed since then, but the College is delighted to have Issam still working in one of its studios.

In addition the Centre has been used for exhibitions and for the student picture loan scheme. Later the only usable room on the second floor has been let commercially either for storage or for creative artists.

Kettle’s Yard Artist’s in Residence

1997-98 Marion Kalmus http://www.marionkalmus.com/

1998-99 Stephen Chamers RA http://stephenchambers.com/

1999-00 Jaun Cruz

2000-01 Jane Dixon ; ; ; http://www.janedixon.net/

2001-02 Claude Heath http://www.claudeheath.com/texts/article7.php

2002-03 Marion Coutts http://www.marioncoutts.com/cv.html

Since 2003, there have not been funds from Kettle’s Yard to support an artist in residence. The studio space that Kettle’s Yard had used is now let by the College – from 2009 to Anthony Smith a sculptor and Christ’s alumnus (m. 2004).

Past and present Levy-Plumb Visual Arts Studentship Holders

2010-2011: Anna Trench

2009-2010: Naomi Grant

2008-2009: Tom de Freston

2007-2008: Verica Kovacevska

2006-2007: Beatrice Priest

2005-2006: Vanessa Hodgkinson

2004-2005: Sarah Howe

2003-2004: Anton Burdakov

2002-2003: Steve Jamison

2001-2002: S J Mockler

2000-2001: S McMillan

1999-2000: J J F Wilenius

1998-1999: Lachlan Goudie

Past and present Visual Arts Award Holders

2011-2012: Rachel Briggs, Helen Taylour, Rosa Uddoh

Charles Darwin and Galapagos Islands Fund

Charles Darwin was one of the most distinguished alumni of Christ’s College, and the most important visitor to the Galapagos Islands. Prior to his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle, Darwin was an undergraduate at Christ’s, and returned to the College in the period immediately afterwards. It was from observations made on this voyage, especially of the Galapagos mockingbirds, that Darwin later drew the evidence to support his theory of evolution by means of natural selection.

Charles Darwin was one of the most distinguished alumni of Christ’s College, and the most important visitor to the Galapagos Islands. Prior to his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle, Darwin was an undergraduate at Christ’s, and returned to the College in the period immediately afterwards. It was from observations made on this voyage, especially of the Galapagos mockingbirds, that Darwin later drew the evidence to support his theory of evolution by means of natural selection.

Christ’s College and the Galapagos Conservation Trust are establishing a lasting partnership between distinguished scientists and researchers with a fund intended to provide support for the activities of people who have shown evidence of distinction in their chosen research field, relevant to present-day aspects of the work originally undertaken by Charles Darwin and which will help to promote the scientific understanding, conservation and long-term welfare of the Galapagos Islands. We work with the Charles Darwin Foundation and the initiative recognises and wishes to commemorate the immense importance of Darwin’s time spent collecting and observing on the archipelago.

The first Charles Darwin and Galapagos Islands Fellow was Dr Mike Stock, a volcanologist, who was in post from 2016 to 2019, and who is now Assistant Professor in Geochemistry and Director of the Earth Surface Research Laboratory, at Trinity College, Dublin. The current Charles Darwin and Galapagos Islands Fellow is Dr Katie Dunkley, a behavioural ecologist, based in the Department of Zoology, who aims to understand the dynamics of animal interactions and ecological networks. Her research focuses on behavioural interactions at a community level to explore how and why animals interact. She is passionate about the marine environment and its conservation, with her previous and future research focusing on coral reefs.

Charles Darwin had a rare genius, nurtured to a considerable extent by his experiences and the friendships generated during his time at Christ’s and during his voyages on the Beagle.

As well as the Fellowship, the Fund supports a Scholarship Scheme (application form).