The sponsor a book scheme has allowed supporters to conserve important texts in return for a personalised book-plate, and an individual conservation report outlining the work undertaken. We’d like to thank every donor who has generously supported the preservation of our collection for the generations ahead.

Amongst these contributions is the sponsorship of two Coptic Arabic manuscripts by Mr Andrew Loader, (m. 1983) a medieval historian who studied the transmission of lost knowledge back into the western world from the twelfth century onwards.

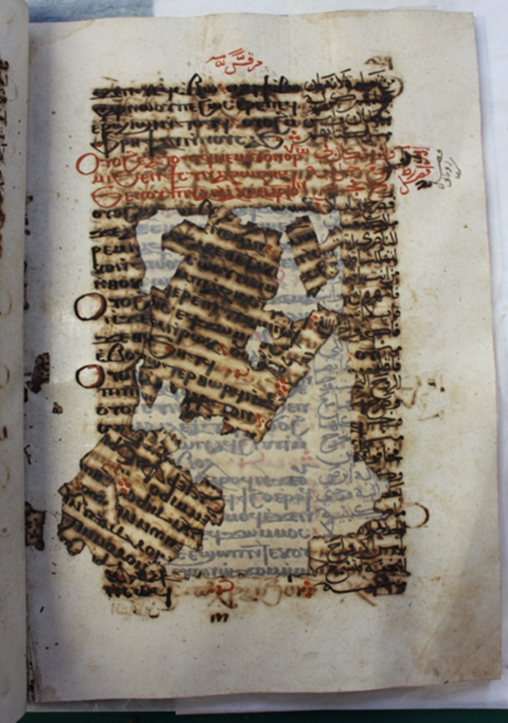

These two manuscripts were in crucial need of conservation. The first is suffering severely from the effects of iron gall ink degradation, dubbed by the British Library as ‘words that eat themselves’. Not only are portions of the text illegible, but in some cases large parts of the page have become completely detached. The conservators painstakingly repatriated each piece to its original position to reconstruct the page, and consolidated it with Japanese tissue paper to stabilise it. Though there is no way to recover the text that has been lost, the conservation treatment has enabled preservation of what remains, though because of the use of other pigments such is the way of iron gall ink that it is not possible to stop the degradation permanently.

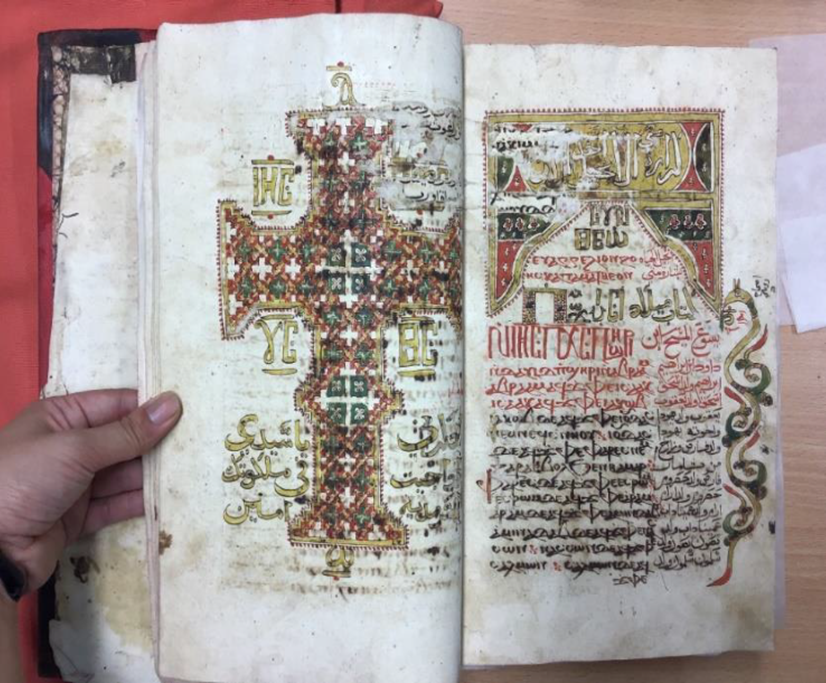

Though little was known about the manuscripts when they were donated, we have gradually started to uncover some of their secrets. One of our college interns recently came to translate parts of one of the manuscripts and from this, determined that it is likely a translation of the Old Testament. We were also excited to disco ver a key at the back of the manuscript indicating where musical notes reside within the margins of its pages.

ver a key at the back of the manuscript indicating where musical notes reside within the margins of its pages.

Another avenue we decided to explore was dating the paper, as we suspect the manuscript may have been produced with the intention to look older than it actually is. We were fortunate enough to have an expert in the field examine one of the manuscript’s introductory pages. They confirmed that the text is a translation of the chapters of the Gospel of Matthew the Evangelist, with a mixture of different hands writing the main content and in the marginalia.

Dating the pages of the manuscript, however, turned out to be trickier than expected. The Arabic palaeography is believed to be anytime between the 15th and 18 centuries. As for the paper: if it is Islamicate wove paper, it’s likely to be around 15th - 16th century, whilst European laid paper would be around 17th - 18th century, yet we’re still unsure as to what type it actually is.

We are continuing in our investigations of these unique manuscripts and look forward to sharing more updates with you soon!