The restoration of Darwin’s Rooms

by Jo Poole

The Darwin Committee at Christ’s College was formed in 2006 to prepare for the anniversaries of the College’s most famous alumnus. It was proposed to restore Darwin's rooms to their early nineteenth-century appearance and open them to the public for the first time since 1909. No drawings or descriptions of Darwin's rooms as he knew them survive. The restoration is based on research by John van Wyhe and Jo Poole into contemporary documents ranging from Darwin’s letters and private papers, recollections of his Cambridge friends, illustrations and descriptions of Cambridge student life in the 1820s–1830s to the physical evidence present in the rooms as investigated by Matthew Beesley and David Bartram. Jo Poole was engaged by the College in 2008 to assist with the restoration. It was her aim to recreate the comfortable and elegant Regency atmosphere the young Darwin would have worked and played in during his time at Christ's.

Darwin's rooms are on the first floor of the south side of the first court of Christ’s College (now room G4). The building dates from the early sixteenth century. In 1758 the exterior of the north side of first court was faced with Ketton stone in the contemporary classical style. By passing through the passage to the Undergraduate library it is possible to view the south side which is still the original clunch and red brick. It seems that no substantial interior structural changes have taken place over time except for the plastering of the ceiling, thus concealing the original beams (similar to those visible today just behind the door of the private chamber and in the Fellows’ Parlour). The sash windows were added during the eighteenth century.

Around 1899 the ceiling plaster was removed or replaced. The central exposed beam may then have been cased with wood as it is today. A modern doorway leading to an adjoining room was added in the northwest corner, which is now covered with panelling. It is important to note that the stairway leading up to

David Bartram, a consultant for the National Trust, conducted an initial inspection of the rooms in 2006 and suggested that the oak panelling around the fireplace was built in situ. The remaining panelling was taken from another source, probably from within the College, judging from the similarity of the friezes. Numerous rough cuts and odd panels (some inserted upside down) also attest to the fact that the remaining panelling was added later. The two ornamental doors on the west side open onto brick walls. The bricks behind them appear modern, at least Victorian. The fluted wooden strips beside the doors were probably added in 1909.

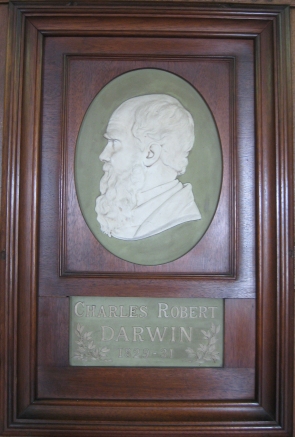

The Wedgwood medallion

Situated between the windows on the north wall in the sitting room is a Wedgwood medallion donated by Darwin's son George Darwin in 1885. The portrait is in white on green jasper and was modelled around 1880. It is from a series depicting Ancients and Illustrious Moderns, which features philosophers and distinguished figures over the centuries. Jasper was created in harmony with the aesthetic associated with the Adams interior, a crucial influence on Regency style. The new Wedgewood museum at Stoke-on-Trent has a copy of the Darwin medallion. A second jasper panel beneath Darwin's portrait reads "Charles Robert Darwin 1829–31”. The date 1829 is a mistake for 1828. A small white ribbon on the underside of the frame reads “Erected by G. H. Darwin. Plumian Professor. 1885”.

The Wedgwood medallion

The interior

The earliest known depiction of the interior of Dawin's rooms is a photograph by J. Palmer Clarke taken in 1909 on the occasion of the Darwin centenary and published in the same year in the Christ’s College Magazine. The furnishing of the room is from the previous century, but is an inaccurate representation of its appearance in Darwin's day. By 1909 the panelling was grained a dark brown with paint and varnish. The original fireplace (now exposed) was covered by a small coal fireplace surrounded by glazed tiles. A gasolier, a hanging gas lamp, hung in the centre of the room. The window seat to the left of the fireplace was removed by 1959 as was the panelling covering the window to the right of the fireplace.

Darwin

In 1933 the rooms, then occupied by the physicist, novelist and College Tutor C. P. Snow, were renovated:

The oak panelling which had been covered by many layers of paint, was cleaned, disclosing the woodwork in excellent condition, and at the top, on the carved frieze, underneath all the paint, bright colouring in blue, yellow and red. This colouring, in addition to being an interesting antiquarian relic, is a distinct asset to the appearance of the room. In some places where the work had failed, it has been slightly and carefully restored; the general effect must now be very much the same as it was when the colours were first put up. Another discovery made at the same time was that of the old clunch fireplace arch behind the modern fittings. The spring of the arch on both sides had been cut away to make room for the later alterations, but the missing parts have now been carefully restored, and the whole effect is extremely handsome. (Rackham 1939, p. 267)

A fine description of the room was published in 1959 in An inventory of the historical monuments in the City of Cambridge, pp.34-5.

W. of stair ‘G’ is lined with panelling, said to have come from elsewhere, of c. 1600 and in five heights with frieze-panels carved with scroll enrichment and a dentil-cornice; the frieze and cornice are in part gilded and coloured. In the W. wall are two projecting doorcases, each with fluted pilaster-strips at the sides [modern additions] and a pedimented entablature of unconventional form having a deep frieze carved with a trefoiled shell, flanking foliated brackets supporting the pedimented cornice and a lion’s mask in the tympanum; the doors are in six panels. The fireplace is original, with chamfered jambs and moulded four-centred head; it is flanked by modern wood pilasters supporting an overmantel, contemporary with the panelling, comprising four arched panels enriched with guilloche-ornament and divided and flanked by reeded and fluted styles; below the S.E. window are some reused panels with similar arched decoration. The door from this set to stair ‘G’ is of the late 17th century.

Darwin's sitting room c. 1959 from An inventory of the historical monuments in the City of Camrbidge captioned "Entrance Court. S. range. Room on first floor, staircase 'G'. Panelling c. 1600".

G4 is today a Fellow’s room and is still used for teaching. In 2008 the mid-twentieth-century carpeting was removed, exposing nineteenth-century floorboards. The perimeter of the boards are blacked and a 13 x 15 foot section in the centre of the room is untreated wood, where a carpet would have been. This is visible in the 1909 photograph. These floorboards are laid perpendicular over an older set of wider boards which are visible just inside the main door and in the bedchamber or cupboard. The under boards in the dressing room and under the radiators (below the window seats) are pine tongue and groove and too narrow and uniform to be original.

Matthew Beesley, Senior Conservator at Fairhaven and Woods Ltd, analysed the paints in several areas of the rooms by examining samples under the microscope, identifying pigments by microchemical tests, fluorescence microscopy and the application of petrological stains to assess the filler materials around pigments. Comparisons were then made with a collection of standard historical microslides.

Several primary samples were taken to give records of original and subsequent redecorations, stratigraphy of paint layer and grounds, and any surface varnishes. The fully illustrated initial report is deposited in Christ’s College Library. Additional tests were carried out before the restoration process began. Susan Smith, Conservation and Design Officer at Cambridge City Council, kindly inspected the site with van Wyhe and after written application gave permission for the Grade 1 listed property to be painted by Fairhaven & Woods Ltd according to their analysis.

Samples 1 and 4 from Beesley’s initial paint analysis report.

The results of the analysis were used to mix the correct paint colours to redecorate the room. The paint finishes chosen were casein distemper for the plastered areas, and dead flat oil for the woodwork. These finishes have been formulated for National Trust properties and are appropriate for use in a Grade 1 listed building, on surfaces such as lime plaster. This approach ensures that the overall scheme is accurate to Darwin's time at Christ's, rather than designed to please the modern eye.

In keeping with the prevalent aesthetic of the period, which did not regard expanses of bare wood as attractive unless it was a rare or tropical hardwood, the panelling was painted green earth in Darwin's time. The frieze at the top of the room was brightly coloured and gilded. The small star marks in the frieze are a technique used to ensure gilded decoration sparkled, especially under candlelight.

Jo Poole made the most unexpected discovery in the rooms. When examining the horsehair seat cushions in the bay windows, she found that both cushions were covered in four layers of different seat covers from different periods. The outer cover was a cream brocade from the last quarter of the twentieth century. Underneath was a green/ brown upholstery fabric from the inter-war period. Below this was a sturdy maroon-coloured cloth from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, which has some basic machine stitching in its construction. Extra padding was stitched below this layer, possibly to stop the itchy horsehairs emerging through the cloth. Finally, the oldest layer was a blue and beige print on a fairly lightweight cotton fabric. This fabric was directly over the horsehair, and has been stitched entirely by hand with linen thread. These layers are the same on both cushions.

The cloth of the innermost layer has similarities with two printed cottons from the Temple Newsam Collection, dated to the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The production of cotton fabrics in England was banned until 1774 to protect the silk and wool industries. The readily available printed cotton goods that flooded the market after the lifting of the ban had wide ranging uses throughout the early nineteenth century.

The cushion covers, as they were found in 2008.

The inner layer with pad stitching and extra upholstery.

The cloth from the innermost layer of the cushions.

The fabric dyes used in the Regency period are not distinctive enough for a chemical analysis to reveal the age of the fabric. Stylistically the fabric is correct for the period of 1828–1831, and the colours are in keeping with those found in the paint analysis of the rooms. As there is no better evidence for the fabric of

Contemporary illustrations consistently show Cambridge undergraduate rooms of the period with curtains.No evidence regarding Darwin's curtains is known to survive. Curtains in the 1820s were lighter in weight than is usual today, their cloth often being of cotton. They were typically plain with contrasting linings made of silesia, a cotton fabric with a twill weave. The fabric used by Poole to create the new curtains for the renovation is the replicated fabric based on the seat cushions as it was of the correct weight and fibre content.

Window treatments shown in contemporary illustrations of student rooms show a single curtain hanging either side of the window, with a single swag above. Contemporary curtain making manuals also detail the correct proportions and construction techniques for this drapery.

In the sitting room, the ceiling is very low and in places only just above the upper edge of the windows. This level could have altered when the plaster was removed in 1899. In order to overcome this, it was decided that the drapery should hang from a wooden cornice as was often the case in the Regency period, providing a solution in keeping with the panelling in the room and also solving the problem of light entering the room above the curtain rail.

Room contents and layout

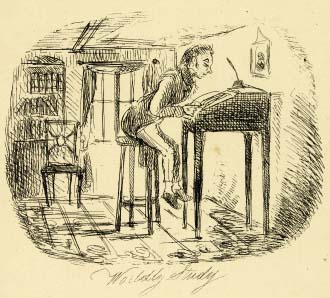

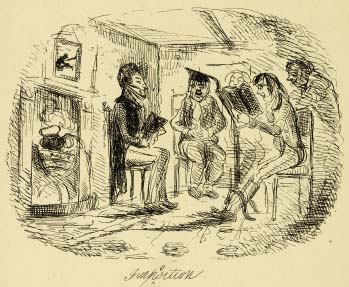

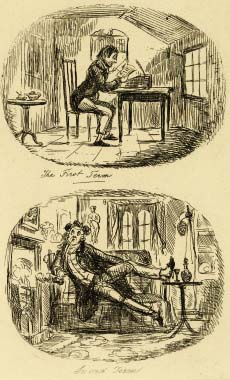

There are several primary resources to draw on as to the layout and contents of college rooms. One of Darwin's contemporaries at Cambridge was William Makepeace Thackery (1811-1863), who was at Trinity College in 1829, during which time he made some etchings of University life. Being cartoons, they are probably accurate depictions of interiors, as he was not trying to prove wealth or status. They record scenes including an earnest student at his study, one more concerned with drink and gambling, another riding in the country and a group supervision.

Etchings of university life in 1829 from Thackeray [1878].

Worldly study

Imposition

First term/ second term

[study/ riding]

The satirical student guide Gradus ad Cantabrigiam (1824) contains a clear depiction of a student’s sitting room. The room is the backdrop for a scene where a Proctor and his men are shown catching a student with a young woman supping at close quarters in front of the fire. There is a carpet with a geometric floral design and border, some pictures on the walls, various chairs, food and wine being taken from a small table covered with a cloth in front of a fire with a hob grate, a fender and tongs. The young man’s cap and gown are strewn on the floor.

Etching of a sitting room from Gradus ad Cantabrigiam (1824).

Quite Unexpected

The following is an extract from the account of a Sizar entitled Struggles of a poor student through Cambridge. Although the author was at Queen's College some two decades before Darwin came to Cambridge, it supports the evidence of later years on the matters of furnishings and room contents.

I now felt myself at leisure to survey, in detail, the fairy land into which I had been so suddenly transported; the rich Brussels carpeting on which I trod, the brilliant chintz hangings which displayed their folds in all the taste and elegance of Grecian drapery; desks, tables, chairs, of the choicest materials and finest workmanship; the whole room actually covered with pictures, which fascinated my untutored taste: among them a variety of portraits, and in particular one of the President was very conspicuously disposed. A large and costly pier glass was suspended over the fire-place; and directly opposite, on the other side of the room, stood another, of corresponding magnitude and beauty. Several large concave and convex mirrors were scattered about. I examined all these and a variety of other objects, to me as novel as they were curious in themselves. At length I rested on the handsome mahogany bookcases. … these were the rooms of a wealthy pensioner. ([Atkinson] 1825)

Private quarters and bedchambers are not seen or mentioned in detail in contemporary sources. Darwin's reference to being snug is similar to C.P. Snow's description in the appendix to his novel The Masters. When talking about the difference in sleeping quarters between the Master and Fellows he writes, "fellows' sets, even those as handsome as mine, contained as sleeping places only their monastic cells." (p.302). This suggests that the bed was in the smaller room off the sitting room, and in the case of Darwin's rooms, the bed could possibly have been in the narrow "cupboard" that now houses shelves for the present occupant's papers. The door forming the cupboard may well be a fairly modern addition. Before the restoration the passage was open at the opposite end, beside the main outer door. This was covered with temporary panelling to facilitate opening the room to the public. The area outside and south of Darwin's room was once known as

Bath Court

It is likely that in the sleeping area, as in family homes, there would have been a chamber pot, and a water jug and bowl for washing. Darwin used the College barber, presumably for shaving as well as haircuts.

Domestic life

Students had to furnish their own rooms, upon taking residence, the following account is given in the Student’s Guide to the University of Cambridge (1862):

The student provides house linens, crockery, glass, some hardware. Linen- sheets, pillow cases, towels, breakfast cloths, in general from home.

Bedders may supply a secondhand set of crockery at a cheap rate, rent teapots etc. Students must buy furniture if in college rooms. A valuation of the articles left by the outgoing tenant will be given to him, and he may take what he likes. In some colleges the fixtures, paint and paper are the property of the tenant, and are taken by the newcomer at valuation, this item is called Income in some cases the fixtures and c. are the property of the college, and there is no charge for Income.

Although this guidance was written some years after Darwin's time at Cambridge it is supported by his accounts and a letter he wrote to his sister Caroline in October 1831.

I want most particularly & directly to know about the Tutor’s bill.— Was there somewhere about 30£. allowed for my furniture? In fact there could not have been, and it is too bad of Mr. Ash, for I wrote on that subject solely to beg of him to subtract it from the bill, before sending it. (Correspondence, vol. 1: 177)

Carpet

The Tutors’ Accounts (T.11.26) have columns for a “W.Drap.” (woollen draper) and “L.Drap” (linen draper), cloth merchants who provided goods for the students. For the “Quarter to Mids.r 1828” “Darwin Jun.r” has “£40.5.6F” under “W.Drap.” This was a large sum, the rent for the rooms being £4 per quarter by way of comparison. It is possible that this records the purchase of a carpet for his rooms.

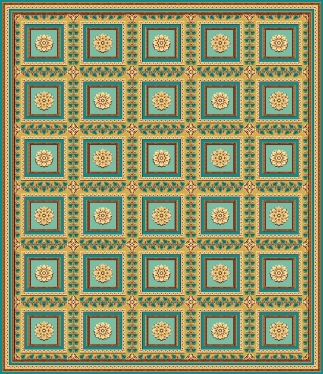

Design of the commissioned carpet for

In Struggles of a poor student, the author mentions "the rich Brussels carpeting on which I trod". Brussels carpets were made with looped woollen pile and were hardwearing and readily available throughout the period. They were manufactured in England, mainly in Kidderminster. The carpets were woven in strips twenty-seven inches wide that were then stitched together to order, often on site, and could then be edged by a matching border.

The Enterprise Weaving Company, based in Kidderminster, has the rights to reproduce some of the original Wilton carpet patterns from the eighteenth century onwards. They still make the carpet to a twenty-seven inch width and then stitch it to order, also producing matching borders for the finished item. After consultation with their historical expert they advised on designs that would have been available to Darwin in 1828. The pattern most closely representing the large, regularly spaced "flowers" on the floor coverings seen in contemporary illustrations was selected and the carpet was ordered in a high quality, densely woven worsted wool. The colours for the carpet were chosen based on the scheme from the window seat cushions. This selection also sits well with the results from the paint analysis. The main carpet has been made slightly larger than the untreated area of the floorboards. A small carpet would probably have been at the entrance to the room, acting as a doormat. There may well have been a hearthrug in place in front of the fire, although the hearthstone is exceptionally large, so this may not have been needed.

Fireplace

Contemporary references suggest that hob grates were the fireplace furniture of choice for student rooms. A hob grate has a raised fire basket in the centre of the grate, with horizontal plates positioned above this on either side. They were made of either cast iron or steel, often with decorated front panels facing the room, and would be bricked in to the sides of the fireplace.

The coal fire would have provided heat and a focus for the student’s room, and the grate was designed so that the kettle could be boiled and bread could be toasted. Students ate breakfast in their rooms at a small table laid with a linen cloth in front of the fire so this form of grate was ideal. It is likely that toast would be made using the fire in the room. There is a boiling kettle thrown on the flames in Thackeray’s illustration “imposition”. Cheese on toast was a popular dish at the time and could be made in flat silver box on the plate of a hob grate.

A fender, probably made of pierced brass, would stop any errant coals from rolling into the room. Fire irons made of brass or steel would have been used to tend the fire. It would have been the gyp’s responsibility to keep the fire stoked. No evidence has been found for a coal box or scuttle being kept at the firesides of student rooms of the period.

Lighting

Oil lamps and candles were used for illumination. The oil lamps burnt colza oil, now known as rapeseed oil, and the candles would have been made of wax or tallow, with wax the more expensive option. Gas lamps were not in use in the colleges until later in the century. Argand lamps were popular at the time, these had a circular wick mounted between two cylindrical metal tubes so that air channelled through the centre and around the wick. A cylindrical chimney, in early models of ground and sometimes tinted glass, surrounded the wick to steady the flame and improve the flow of air to give a better light. They were more expensive than the common oil lamps and required a supply of high quality liquid oil such as spermaceti oil. The small wooden ceiling rose in the sitting room probably does not date back to Darwin's residence. Although oil lamps and candle holders were hung from the celing at the time, it was unusual in domestic interiors. At Down House, rooms are lit by oil lamps converted to use an electric bulb. This seemed the best solution for the rooms at Christ's due to fire restrictions and for practical reasons regarding the ongoing use of the room for College life. The localisation of the light sources helps to create an authentic atmosphere. It is clear that Darwin had candles in thw room, but the use of oil lamps is an assumption.

Costume

Male attire at the turn of the nineteenth century underwent several major changes, the most notable was that breeches and stockings gave way to trousers for almost all occasions. The university initially rejected this new style of dress regarding it as too informal, permitting its adoption only in 1824. The etching right shows a student in a Bachelor of Arts gown with trousers, having just received his degree. Undergraduates wore gowns determined by their colleges with the university stipulating that they reach at least to the knee, University gowns were adopted upon graduation. The three categories of students (Fellow Commoner, Pensioner and Sizar) were easily recognisable by their different gowns. Fellow Commoners gowns were trimmed with gold lace, and Sizar’s gowns would have been made of an inferior cloth to those of the Pensioners. The individual college gowns have changed very little in style over the years.

Etching of student from Gradus ad Cantabrigiam (1824)… The caption translates as “safe after such a shipwreck — I am bachelor of Arts”.

Etching of a Christ’s Pensioner’s gown c. 1830–1840 from [Whittock c. 1840.]

According to Harraden’s Costumes of the University of Cambridge (1805) on Pensioner’s dress: “Academic Habit is a Black Gown, made of Prince’s Stuff, with Black Velvet Cape and Facings. The Cap is Black Cloth, with a Silk Tassel." 'Prince's Stuff' is a woven cloth of wool mixed with silk.

Right is an etching of a Christ’s Pensioner from the mid-nineteenth century. This gown is similar to the undergraduate gowns worn in College today, but a little longer. It is probably like that worn by Darwin. The cap does not appear to have changed in size or form over the centuries, still being made of black wool felt with a silk tassel. Darwin would have worn his gown in College for Hall, Chapel and lectures.

Other objects in the rooms

The story in Darwin's Autobiography, p.44, reveals that there was a looking-glass, percussion shotgun and candle in the room. A pier glass is mentioned in several contemporary desciptions of student rooms, and was a popular choice of looking glass during the Regency period, it is a tall narrow mirror, designed to be placed between windows. This position would be advantageous in terms of lighting the subject reflected in the glass. Unfortunately, this location is not practical for the room restoration due to the Wedgwood medallion now in this place. Darwin collected fine engravings for his rooms

Also resident in the rooms was a dog called Dash. William Darwin Fox's records show that a considerable number of dog whips were purchased during his time at Christ's. It is entirely possible that his cousin Charles also used these. Darwin kept a horse in Cambridge from October 1830, so there may well have been some of the clothing and accessories necessary for riding in the room, but tack would probably have been stored at the stables.

Several contemporary sources show tall desks with sloping tops for students to write at, but as Darwin used a microscope and worked at his beetle collection, this would not have been practical. A level surface positioned in good light is more likely. At any rate Darwin must have had a table large enough for the eight members of the 'Glutton' or 'Gourmet club' to dine together in Darwin's rooms.

Shooting and collecting

There would have been a number of articles in the rooms relating to shooting and collecting insects. There were also bird skins – many on their way to cousin William Darwin Fox. In 1828 Darwin's family contributed £20 towards the purchase of a new double-barrelled shotgun. This was a top of the range percussion gun, manufactured in Birmingham or possibly London. He also used no. 7 shot, a copper powder flask, shot belt, caps and a cleaning rod with linen patches. Percussion guns were patented in 1818, becoming very popular in the 1820s as they were less susceptible to wet and damp conditions than their predecessor, the flintlock.

Darwin used a sweeping net, as seen in the cartoon by Albert Way, to collect insects. Collecting nets receive a considerable amount of battering so they are very rare. A net belonging to Darwin is at Down House. A similar, antique collecting net has been lent by Ian Ferguson for display in Darwin's rooms in 2009.

Acknowledgements

Jo Poole was greatly assisted by Jane Sargent (fine art conservation), Ali Fletcher and Pete Davenport (antique weapons dealer).

References

Anon. 1824. Gradus ad Cantabrigiam: Or, new university guide to the academical customs, and colloquial or cant terms peculiar to the University of Cambridge; observing wherein it differs from Oxford. London: J. Hearne.

Anon. 1862. Student’s Guide to the University of Cambridge.

[Atkinson, S.] 1825. Struggles of a poor student through

Autobiography: 1958. The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand–daughter Nora Barlow. London: Collins.

Correspondence: Burkhardt et al eds. 1985–. The correspondence of Charles Darwin. 16 vols.

Harraden, Richard. 1805. Costume of the various orders in the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: R. Harraden

Rackham, H. ed. 1939. Christ’s College in former days. Being articles reprinted from the College Magazine.

Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of

Snow, C. P. 1972. The Masters. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.