Jilly Luke - English

It's not often that you get to write your dissertation about someone with whom you’ve been in a romantic clinch. When I limbered up to start writing on John Milton’s Paradise Lost, however, it was in the knowledge that I had locked lips with the author himself. It is, after all, traditional at Christ’s College to give the bust of Milton that resides in hall a kiss on your birthday. Whilst Milton was no prude, I’m not sure how he would have felt about kissing *everyone* in college, and suspect that had he been in attendance in more recent times his favourite of the newer college traditions probably would have been jumping fully clothed into the swimming pool after your exams.

John Milton came to Christ’s in 1625 at the tender age of 16 and was given the nickname “the Lady of Christ’s” because of his “effeminate ways and youthful looks”. Thankfully, we have actual women attending the college nowadays, making such tiresome misogyny something that will be met with a withering put down from some of the fiercely intelligent women who stalk the corridors of the college. Tiresome misogyny, as it turned out, was very important to my dissertation—more of which later.

John Milton is one of Christ’s most famous alumni, making the college a very good place to undertake work about him both in a practical sense and in a more wishy-washy “it feels right” sense. Practically, it means that college have a very fine collection of Milton’s works, both in modern critical editions and, crucially, in first printed editions. They have some eight copies of the first printing of Paradise Lost, for example, and the library staff, friendly and helpful as they are, are more than happy for undergraduates to have a little look at them. The college also produced a very good online resource for studying Paradise Lost, which is well worth a look for anyone interested in getting a flavour of what it is like to study English at university. You can find it here. In the wishy-washy “it feels right” sense, it means that you can visit the rooms Milton was rumoured to keep as an undergraduate, the mulberry tree planted in the year of his birth, look at his portraits (and that bust) in hall and generally tread the paths that he trod around college. It also allows you to feel a part of the academic community that first birthed Milton and then fostered a long and proud critical Miltonic tradition.

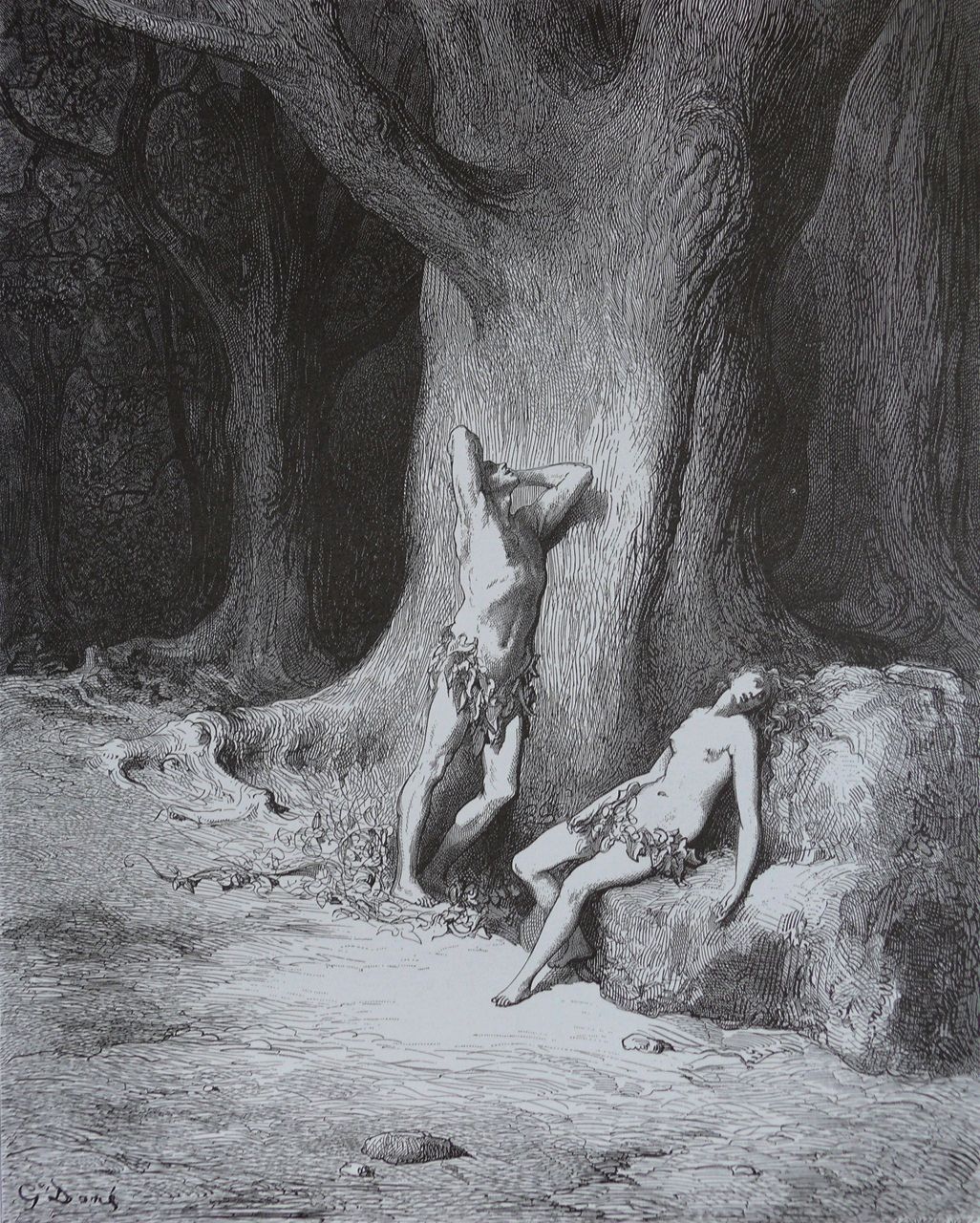

But before we go any further, a quick plot summary of the poem itself. Paradise Lost is a long poem written in 12 sections which traces the story of the fall of Satan from Heaven, the creation of Adam and Eve, their first days in Eden, their temptation and fall and their expulsion from the Garden via some wars in Heaven (that bit didn’t really do it for me) and quite a lot of chat between Raphael and Adam about the creation of the world and what God is like. It is some of the most engaging and beautiful poetry written in English, and is, at times, profoundly moving. The creation account in Book 7 is particularly epic (in all senses) when God creates the seas: “boundless the deep / for I am who fill infinitude”.

Unfortunately, I promised you tiresome misogyny, and the critical tradition around Paradise Lost does not disappoint. Eve is routinely held up, both in the period in which Milton was writing and in more modern times, as the cause of the Fall of Man (the start of sin in the world). The basic premise of my dissertation was that this is unfair, and that Milton actually puts the blame far more on Adam for the Fall than he does on Eve. My argument was that the Fall of Man was actually better understood as an act of falling that happened between the creation of Eve and Adam’s eating of the apple, with Adam consistently messing up in the period between those two points and so effectively causing his own fall and that of Eve because of his inability to submit his passion for Eve to his reason.

My dissertation spent a lot of time redressing the balance of previous criticism, arguing that the fact that Eve names the plants is crucially important—indeed, as important to the poem as the fact that Adam names the animals, an act which has spawned some very long and thoughtful critical texts, whereas everyone, feminist critics included, plays down the fact that Eve names the plants and treats is as a bit of a non-event. It was only through appreciating Eve’s special relationship with the plants of the garden that we could understand why she is so vulnerable to temptation by a tree.

I have been fortunate enough to come up to Cambridge at a time when there is a broad and serious awareness of feminist issues, and there are lots of opportunities to talk about issues to do with sexism both at an institutional level and more informally with other students. These discussions have had a big impact on my academic work. One of the great things about English as a subject is that it allows you to develop your own critical voice by taking in academic theory and criticism alongside cultural debate. My ‘feminist’ reading of Paradise Lost was very different to that of previous generations of feminist critics, but it was wholly rooted in close reading passages of text and I was able to engage within that academic tradition in a way that made me feel like I had something unique and useful to contribute and in a way that was an honest reflection of my own feminist leanings. There is a lot still to be done to address the way in which women are treated in our society and around the world, and undertaking a project like this at Cambridge allowed me to address a small area of academia in which a woman has been mistreated and misrepresented and to sharpen my critical tools in order to address such mistreatment in other places.

Further Exploration

Darkness Visible - an interactive resource for studying Paradise Lost