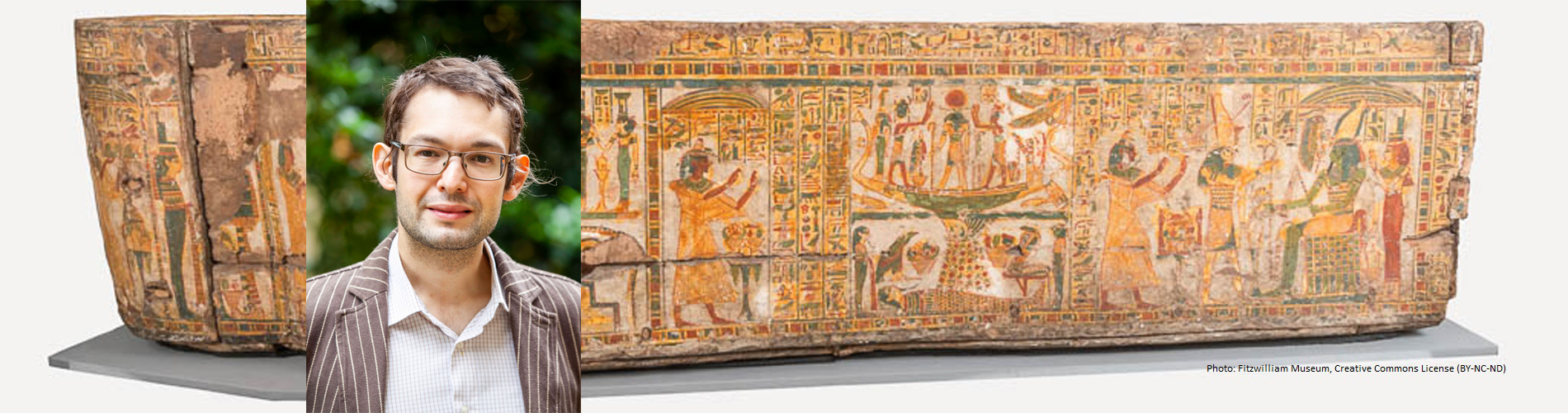

Egyptologist Dr Alex Loktionov uses papyrus and pottery to understand conflict over ancient Egyptian coffins. Here, Christ’s very own ‘coffin boffin’ tell us more about why coffins - and their contents - were so important to ancient Egyptians.

Mention Ancient Egypt and most people think of the pyramids. But only the earliest Pharaohs like Khufu were buried in them; often rich Egyptians were buried in a tomb within a necropolis (city of the dead). Made by highly skilled craftsmen and containing precious metals like gold, coffins were expensive items that were regularly bought, sold, broken up or stolen.

Dr Loktionov said:

“A reasonable coffin would cost about as much as a donkey – which was the closest thing people would have to a car.”

Ancient Egyptians often went to court to dispute ownership with family members or to prosecute thieves. Dr Loktionov finds evidence on ostraca which, he says, is ‘a fancy word for broken bits of pot’ as well as on writing material prepared from the stem of a water plant known as papyri.

And he is astonished by the scale of litigation:

“So far, I have discovered 36 different texts mentioning coffins in legal settings, which means that they were among the most common triggers of judicial dispute.”

Another source is the huge book containing writing and tomb engravings known as the Description de L'Égypte produced by a group of scholars and scientists who travelled with Napoleon Bonaparte’s army from 1798-1801.

A tomb was built as a ‘house’ for the dead and would be filled with everything the deceased might need in the next world including models of servants or ships.

Prayers or offerings made by relatives were believed to turn pictures of food on the walls of the tomb into actual nourishment. The central element of the tomb was the stone sarcophagus with one or more wooden coffins inside it.

Coffins were inscribed with spells from the Book of the Dead – a guidebook to help the deceased navigate the underworld judgement and find eternal happiness. Those who failed could expect to be eaten up by the monster Ammit – one third lion, one third hippo and one third crocodile. Dr Loktionov said:

“Being devoured in this way was called ‘dying a second death’ and represented utter destruction forever.”

Dr Loktionov was born in France to Russian parents and educated in the UK. It was this multicultural background – growing up speaking three languages and reading two different scripts - which got him interested Egyptology. He said:

“I would like to say that I played with toy pyramids as a child but that’s not the main reason. Being originally from Lyon helped as well – it’s the city emperor Claudius was born in, and it’s one of the finest Roman sites in Europe.”

Strictly speaking, an Egyptologist is someone who can read hieroglyphs whereas an Egyptian archaeologist works on non-textual remains. In practice most academics do a bit of both.

As a picture-based language hieroglyphs might look easy, but the language took hundreds of years to decode. Dr Loktionov said:

“If you look at a picture of an owl, actually all that means is the letter M – just one sound. It has nothing to do with owls whatsoever!”

As a language that was written down continuously for 3000 years, it is a complicated system of combined sounds with several hundred signs.

If you choose to study Ancient Egypt at university not only do you become part of a ‘close knit community of people who really love this stuff’ says Dr Loktionov, but you will also have your entire degree to learn the language, get the opportunity to read old, beautiful literature and see the greatest archaeological sites in the world.

The ‘Coffins in Context’ conference taking place at Christ’s next week will look at the place of coffins in Egyptian society. Dr Loktionov said:

“For a very long time, we have thought of coffins as something to do with death (like in our own culture), but perhaps we should think of them far more as something to do with life and wealth.”

Christ’s College hosts the Lady Wallis Budge Fellowship in Egyptology, of which Dr Loktionov is the 12th Fellow, which has funded research into Ancient Egypt since 1934.

The Egyptology Website.

Listen to Dr Loktionov talking about coffins and his fascination with Egyptology on Cambridge105 (starts 15:30).

Christ’s College will host the hybrid Coffins in Context conference with the Fitzwilliam Museum from 22-24 February 2024.