Sarah Choi - History and Philosophy of Science

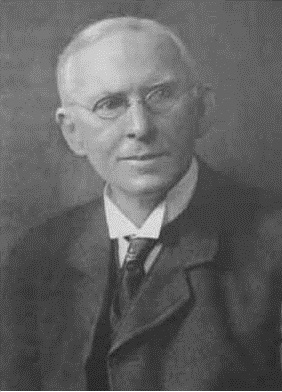

Hi, I’m Sarah, a third-year medic at Christ’s College. In your third year of undergraduate studies as a medic or Natsci (someone who studies natural sciences), you are able to choose from an array of science-related courses. I chose to study History and Philosophy of Science (HPS), and as part of my course I wrote a dissertation. I was interested in investigating, in some form, the conflict between Science and Religion, and after reading a few general books such as Roman Catholicism and Modern Science I came across Sir Bertram Windle. After further research it was clear that although at his time he was a popular Christian apologist (someone who argues in favour of Chritainity in their writings), historiography reveals that there has been little interest in him. Furthermore, Windle seemed to be an interesting figure to investigate as he was writing at a time when evolutionary theory was undergoing major developments as it became synthesised with new sciences such as genetics, and, in this context biological evolutionism continued to provoke controversy. By paying attention to Windle’s work, I was able to discover the thoughts and concerns of contemporary scientists, theologians and the public.

Hi, I’m Sarah, a third-year medic at Christ’s College. In your third year of undergraduate studies as a medic or Natsci (someone who studies natural sciences), you are able to choose from an array of science-related courses. I chose to study History and Philosophy of Science (HPS), and as part of my course I wrote a dissertation. I was interested in investigating, in some form, the conflict between Science and Religion, and after reading a few general books such as Roman Catholicism and Modern Science I came across Sir Bertram Windle. After further research it was clear that although at his time he was a popular Christian apologist (someone who argues in favour of Chritainity in their writings), historiography reveals that there has been little interest in him. Furthermore, Windle seemed to be an interesting figure to investigate as he was writing at a time when evolutionary theory was undergoing major developments as it became synthesised with new sciences such as genetics, and, in this context biological evolutionism continued to provoke controversy. By paying attention to Windle’s work, I was able to discover the thoughts and concerns of contemporary scientists, theologians and the public.

The title of my dissertation changed several times from the initial planning process to the finished product. The title of it came about after reading a work by Jonathan Topham who coined the term ‘safe science’: science accessible to Catholics in a suitable form, so that they would be up-to-date with the current developments in science without feeling threatened or anxious about the content. I argued that Windle’s writings and their success were motivated by a need for a safe science for Catholics.

Rapid scientific development during the early twentieth century caused two major problems. First, some of the facts and theories presented by scientists seemed to disrupt the peace of the Church. Secondly, the overwhelming influx of new scientific facts increased the potential for Catholics to misinterpret them and say things that reflected badly on the Church. Windle therefore hoped to use his authority as a trained scientist and Catholic to reconcile science and religion in a way suitable for Catholics; to try to resolve any misconceived ideas.

I divided my dissertation into three chapters. In my first chapter I briefly examined how Windle, coming initially from a Protestant background, became at first agnostic then later a fervent Catholic. In this section I also investigated what influenced Windle to become a writer and a physician. I concluded that from his reception to the Catholic Church, his faith was of central importance to him. It became clear that his development into a Catholic was due to a combination of inter-linking factors; the evangelical childhood home that drove him away from Protestantism, his father’s dissuasion from a life at sea, an early introduction to science, his fascination with medieval architecture and Gregorian music (this was what attracted Windle to the Cathedral in Birmingham which sparked his conversion, and the anti-Catholic literature given to him by a friend which instead of dissuading him from Catholicism had the opposite effect. In writing this chapter it became clear that Windle genuinely loved writing; underscored by his many published works on anatomy and his earlier years and his later apologetic works. As a scientist and Catholic, the necessity for establishing a union between faith and science became of greater importance. He believed that no truth clearly established by science could conflict with the truth revealed by God. He set about conveying this to the public through his works. It is clear however that it was his faith, and in particular the need to disseminate the correct theories between religion and science, that encouraged him to write more and more on these maters. Some of the last words to be written by his pen beautifully illustrate this, “I have tried to lead a Catholic life, and do what I could for the Church, and I am sure in my heart of hearts that God will not desert me at the end”.[1]

The second chapter discussed how Windle was able to reconcile religion and science and why he saw the need to do so. As a Catholic and someone who was trained in science and medicine, Windle saw himself in a position to explain and comment on controversial issues that were being discussed at the time. This was done by looking at specific areas in science that were seen to conflict with the Catholic faith. Windle set out to provide science that was available to all, especially to Catholics who may not have been so confident on the technicalities of scientific issues. It was clear that he reconciled the two areas by involving other theologians and scientists and by using examples to illustrate his points. He believed that science and religion were both fields that dealt with truths shown by God. What Windle was trying to reconcile was not science and religion, but prevailing scientific beliefs and religion. The main concern for Windle was those people who represented both fields that created conflict and division among the population; especially those scientists who wrote for the press, and religious leaders who were out of date with science and gave misleading information. His books intended to address this latter problem by providing Catholics with current scientific information. Although Windle promoted reconciliation, it was clear, in his mind religion overruled science in any conflict. This was clearly evident when areas of science disagreed with aspects of religion as, in these situations, Windle attempted to align the scientific theory with religious concepts. When this was not possible, he explained that the fault lay in the scientific theory.

Chapter Three examined how Windle presented science to Catholics in a way that enabled them to understand it without fear - in the form of ‘safe science’. He discussed ideas that the general reader would already be familiar with and then developed them throughout the chapter, by stressing the importance of the role of the Bible and science. I was inspired by the work of Aileen Fyfe who in her book discussed how writers presented material in a ‘Christian tone’. It was evident that Windle’s method of writing also provided a way to ‘train’ Catholics’ minds to think about and approach problems in a more informed manner, while never forgetting the central importance of God.

Windle stood out from the rest of the other popular Catholic authors of the time in many ways. For one, many contemporary authors became popular due to their innovative ideas in reconciling Christianity and science. Windle, however, became popular for his ability to provide Catholics with succinct science that served to reflect the glory of God.

Windle’s characteristic clear thinking, combined with his love for Catholicism, led him to take an interest in questions that arose out of the relationship between science and religion. He wrote in a style that most people could understand, not just for those who were educated or familiar with the subject matter. His ability to compress the results of modern research work made the topics under discussion accessible and relevant to the wider the population. Various contemporary reviews made it clear that Windle succeeded in what he set out to achieve. As the leading Catholic weekly, The Tablet said, “He stands pre- eminent as the Catholic scientific apologist.”

I thoroughly enjoyed studying HPS and believe it has enabled me to develop extra skills that I would not have otherwise. I hope my brief article has been of use and good luck with your application!

[1] Monica Taylor, Sir Bertram Windle, A Memoir (London; New York: Longmans: Green, 1932), 405.